By Ruth Stanley-Aikens

Expanding definitions

Trauma-informed approaches have begun to expand to include being violence-informed; this offers a more complete approach that incorporates an understanding of systemic and structural harm:

“Violence” was added to trauma-informed approaches to emphasize the broader structural violence that influences and shapes interpersonal experiences of trauma, an individual’s health and well-being, and engagement with services. [Trauma- and violence- informed] approaches seek to dismantle power imbalances within health and social service settings. This is particularly important for individuals who have been disempowered or whose voices have been silenced or talked over.

Western centre for research and education on violence against women and children

Trauma and violence-informed (TVI) practices are a confluence of best practices which put the person or community we serve at the centre of a safely supported collaboration, using tentative and strengths-based language, and begin from a dedicated position that the community we serve are the experts in their lived-experience(s). Therefore, the person or community we serve must be treated as partners at all stages of program and service development.

It does not stop there; TVI practices can also protect service providers, social workers, therapists, et al, from developing vicarious traumatization. The way we behave on the job, can be aligned to reflect low-impact debriefing, and by adding an empathetic vs sympathetic approach, can help to avoid the distress of vicarious traumatization.

A collaborative approach starts from a position of curiosity. It starts and ends with various forms of, “how can we work together to plan the way forward.” It avoids attempting to define a person’s trauma experience. Ultimately, this approach contributes to creating programs and services that meet the community member’s needs.

The confluence

Safe spaces

We should never promise to provide a safe space for others. We have a responsibility to exercise due diligence in supporting a safe(r) environment; however, safety is defined by the person/community we serve.

Persons with lived experience of trauma (PWLET) can feel safe one moment, and feel unsafe the next, despite the facilitator or service provider engaging in every best practice known. It is our responsibility to acknowledge when something has changed for an individual, asking respectfully, “I’ve noticed, (insert observable phenomenon)” and ask, “What can I do to help/help you feel safer?” This shows both concern and respect for the person who may no longer feel safe. It begins a collaboration on next steps.

We must always be transparent. We “support safety” in conversations, collaborations, programming and service delivery. Language is important.

A relational approach

Collaboration is not just a word; it is the driving force behind a trauma-informed approach. This starts from a position of understanding that we, as service providers are not the experts in the trauma a person/community has experienced (systemic and community-based macro and micro aggressions of racism, sexual assault/harassment, early childhood adverse experiences, to name a few) and we do not know the best way to create programming to meet their needs. We can only know when we consult. We need to partner in the work.

This does not exempt programs/service professionals/institutions from their responsibility to understand the potential impacts of trauma, or existing models of service. Each person must understand trauma, and the ways that trauma may influence coping, communications and needs. Service providers must be able to identify that dissonance in relationships may be occurring due to protective coping skills, and act to build trust with their client.

There are institutional limitations influencing the service an organization can deliver, and sometimes clinical best practices further limit the parameters of a program. Without transparent collaboration from the outset, these limitations and other factors can create conflict, lead to the loss of trust and credibility, result in financial repercussions and harm the community you intend to support.

Strengths-based language

All too often we stumble and advertise opportunities for engagement to improve people’s lives. For example claiming a program will “reduce veterans’ experience of isolation,” would be a hierarchical and assumptive statement. We must never define what another person is feeling or what is true for them. When we do, it can create conflict and interfere with our credibility because we can be wrong. No two persons experience a traumatic event in the same way.

Instead, we need to use language that brings people in, such as “to bring veterans together.” A strengths-based approach speaks to what is positive. Although people experience many challenges which can result in symptomatology, we need to remember that humans want positivity, despite being threat sensitive. Hammond and Zimmerman describe a strengths-based approach as, “Rather than the traditional perspective of engaging a person with a problem orientation and risk focus, a strengths-based approach seeks to understand and develop the strengths and capabilities that can transform the lives of people in positive ways.”

A strength-based perspective informs not only how we provide services but also how we promote them to potential participants (i.e. how we offer answers to the question “what’s in it for me?”). The way messages are received by our community partners does not always reflect what we intended to communicate, but we can do better if we listen. When we collaborate, we may find out that a portion of the population we serve is feeling disconnected; we might then advertise:

[Name of program] is a place to bring [identified PWLET community] together in a place that supports individual safety, to connect, support, and engage.

Finding a strengths-based approach to describe what you intend to do is important. We cannot make the mistake of defining another person’s experience.

Proactively preventing re-traumatization

Re-telling a trauma narrative may be a component of trauma therapy – not always, but it can be, and it must involve consent and the rationale for doing so. However, in other service relationships, re-traumatizing the individual and others can happen unintentionally, when trauma content is described.

For some, they urgently want to tell their trauma experience. Containing that discussion can take gentle boundary setting. Engaging in this boundary setting can feel uncomfortable but it is necessary. No one wishes to lose the connection with a client because the client feels guilt or shame for disclosing their deeply personal experience to you prematurely, or without need.

For others, their priority is to not retell their trauma experience to people; often they have been asked repeatedly to describe their experience by various service providers, sometimes without knowing why.

In either scenario, people can suffer as a result.

Consider, “It is not the event that determines whether something is traumatic to someone, but the individual’s experience of the event and the meaning they make of it.” The internal meaning can affect all aspects of a person’s life/coping/ways of being in the world.

Instead, asking them about how this trauma has impacted them.

Often, what happens after the traumatic event determines its effects. Understanding these influences helps providers work to avoid retraumatizing the community we serve.

Putting TVI practices into play within the workplace

We all experience trauma, grief, forms of institutional betrayal and moral injury. All experiences can have effects on our coping, communication style, relationships and capacity.

Notice when reactions to a conversation are responded to out of proportion to the subject being discussed; this is a good indication that someone may be suffering, and that person may even be you. Prioritize the relationship, be transparent, mend injuries to the relationship. Notice when there are unresolved feelings. Approach from a genuine position of curiosity, or intention to connect with the person and try to find a way through.

Low-impact debriefing can be very useful when seeking support in the workplace. TEND Academy offers resources that instruct on ‘debriefing without sliming’ or avoiding giving trauma content to another person which can make them vulnerable to vicarious traumatization. Using an empathetic lens, with a slightly different definition, can also be helpful.

Steve Davis writes about the benefits of empathetic facilitation, which can be applied to the concept of mutual support to make it more effective:

… coming from an empathetic perspective, you understand what the other is feeling but you don’t necessarily go there with them. Instead, you view them as capable of working through the issue at hand. To be empathetic to someone in pain, you might say something like, “I sense that you’re hurting. What do you need right now?”

Steve Davis: Be empathetic not sympathetic

This definition assumes the person who needs support is a competent problem solver. It doesn’t impose meaning to what they have been through – only the person who experienced the trauma is positioned to describe the impacts of their experiences.

Workplaces could benefit from adopting a similar approach to reduce the contagion of trauma material contributing to vicarious traumatization with clients and between colleagues.

From ideals to action

Applying trauma- and violence-informed principles is a confluence of best practices culled from training on counselling, the expert advice of the people we serve, debriefing without harming others, and our own self-knowledge. Using a TVI approach in all aspects of life, with colleagues, clients, community members, family and friends, can reduce harm and mitigate suffering.

References

Bolton, MJ et al, Trauma Informed Tool Kit 2nd Ed., (2013), Klinic Community Health Centre, https://trauma-informed.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/trauma-informed_toolkit_v07-1.pdf

Communities together for children, (2025), What is trauma, EarlyON Child and Family Centre Northwood, https://www.ctctbay.org/community/community-partner-table-resources/trauma-informed/what-trama

Davis, S (2013),Be empathetic not sympathetic, Facilitator U: awakening conscious leadership, https://facilitatoru.com/facilitation/be-empathetic-not-sympathetic

Tend, Tend Academy Ltd (2025), Low impact debriefing, https://tendtoolkit.com/low-impact-debriefing-strategy

Western centre for research and education on violence against women and children, (2020), Learning network, Issue 31: Trauma- and violence- informed approaches: Supporting children exposed to intimate partner violence, https://www.gbvlearningnetwork.ca/our-work/issuebased_newsletters/issue-31

Zimmerman R. and Hammond W, (2012), A strengths-based perspective, Homeless hub, https://homelesshub.ca/resource/strengths-based-perspective

Ruth Stanley-Aikens, MSW, RSW

Ruth has worked at the provincial and federal levels for over 40 years. She is currently the Special Advisor on Trauma at the Sexual Misconduct Support and Resource Centre, which provides services for Canada’s military and extended defence communities. Ruth is trained in a number of clinical modalities with a focus on dissociative coping, and has extensive experience working with survivors of sexual trauma including war-related trauma. In 2025, she was awarded the King Charles III Coronation Medal in recognition of her service to trauma-informed practices within the Canadian Armed Forces/Department of National Defence.

Read more of Connection

- The continuing evolution of trauma-informed praxis

- Spotlight: 2025 Student Bursary Recipients

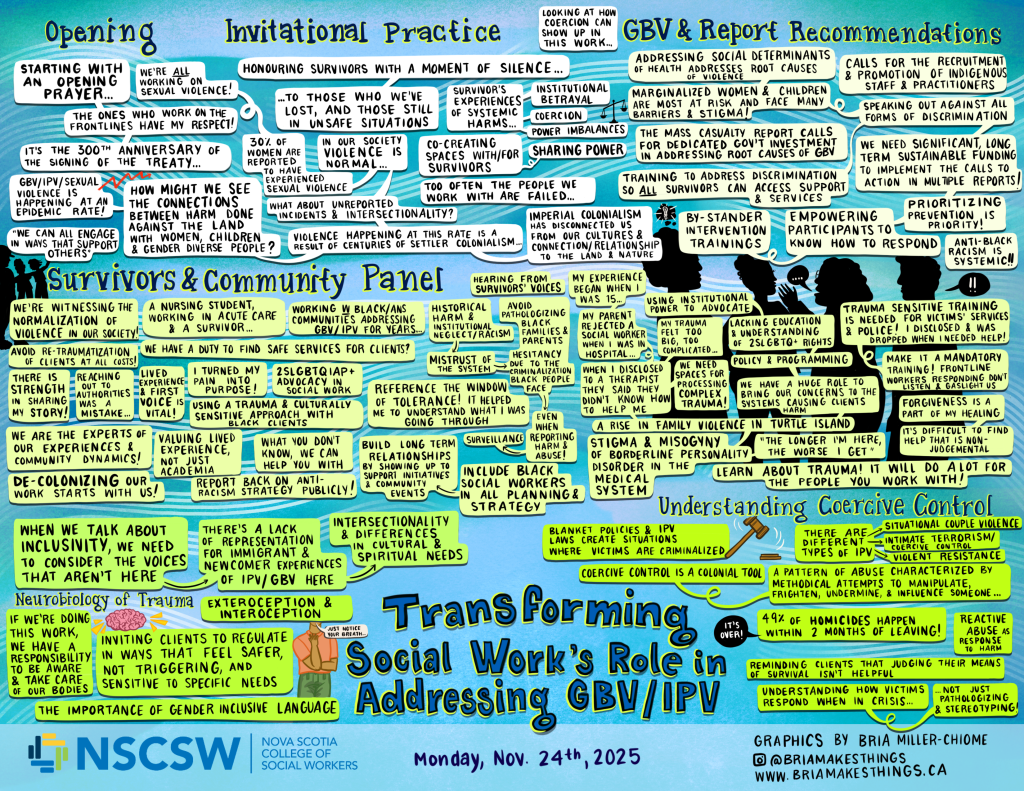

- Responding to the epidemic of gender-based violence: Reflections & invitations for the 16 Days of Action

- Healing in the crossfire: Clinical social work in a genocide

- Healthcare erosion: “Why didn’t you press the button?”

- Food, Body, and Bias: Why Your Words Matter

- Developing a standard of care for social work practice with people who use alcohol and drugs

- Book review: Active Hope

- NSCSW Awards: A spotlight on our community

- Spotlight: 2024 Student Bursary Recipients