On May 2, 2025, the NSCSW held our virtual mini conference: Building Connections & Activating Hope. The intent of the professional development committee was to develop a collaborative learning experience that would reinforce relationality and critical hope among participants.

Design challenge

How can social workers activate critical hope in ourselves & others so we can create and sustain change?

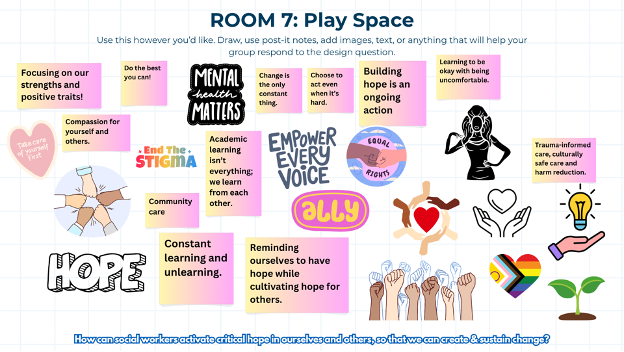

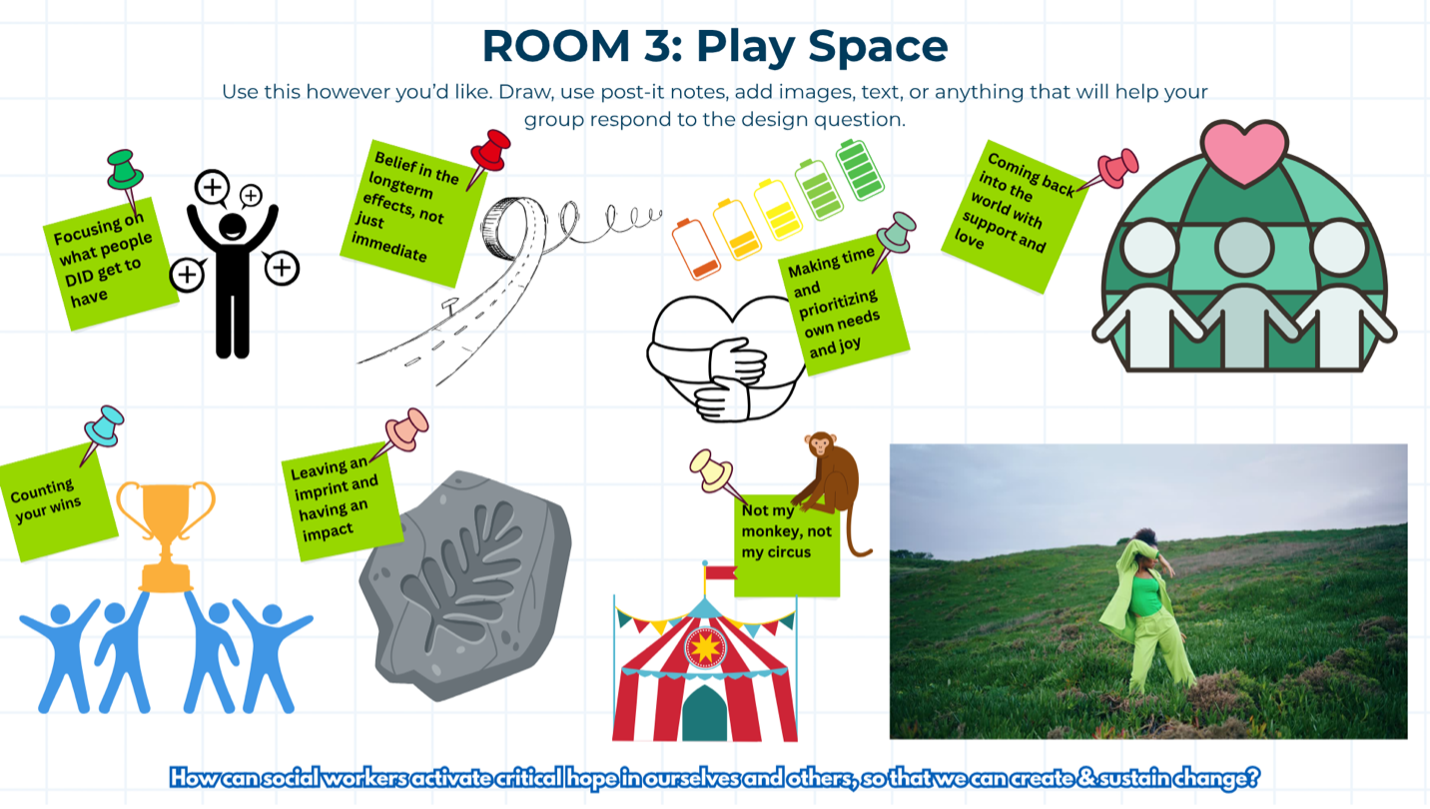

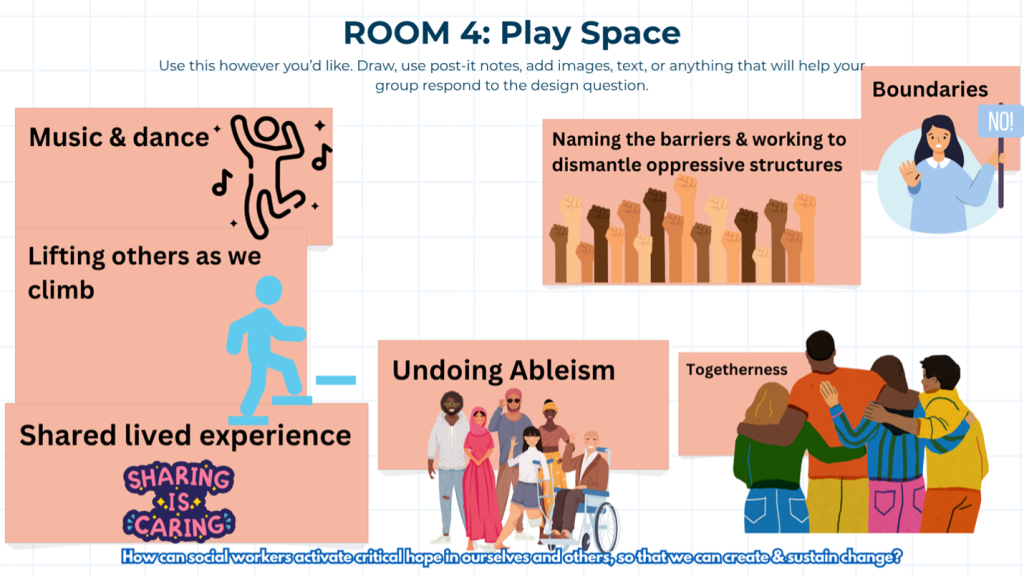

The afternoon session invited members to delve deeper into the concepts that had been explored during the morning, and use digital whiteboards via the Canva application to co-create and share ideas. We had ten small groups who created interesting, playful, and thoughtful images and reflections. A few are shared below.

Many groups highlighted the importance of being active in applying anti-oppressive practices and unsettling social work. They expressed that critical hope requires ongoing reflection and action, that learning and unlearning were important, and a need to prioritize non-dominant ways of knowing and being in learning.

Attendees also discussed the importance of prioritizing self-care and joy in this work, while holding onto empathy and compassion for others. There were many who shared the importance of building relationships in professional networks, and with family and friends.

Our Code of Ethics & Standards of Practice are clear in the role of social workers engaging in socially just and critical social work practice. It is important that social workers take an active position resisting settler colonial and white supremacist ideologies, systems, and practices in our work and in ourselves.

Learning in practice

While the design challenge was ultimately a successful activity, it came with a few challenges. It was not known at the time of the conference that Canva allows a maximum number of contributors, so not everyone was able to use the application at the same time. Additionally, not all members were familiar with the application and the learning curve for using this resource was a barrier for some.

However, many attendees reported that the digital whiteboard was an interesting and engaging way to contribute to the discussions, and social workers from across Nova Scotia successfully shared critical thoughts, hopes, and reflections. Our participants at the mini-conference, as well as our members across the province, are individually and collectively working towards safe(R) social work practice.

In case you missed it

While the interactive activities could only be experienced live, the morning sessions were recorded and are available to watch on YouTube. If you were unable to join us for the entire session, you can catch up:

Staff members Tyler Colbourne and Bria Symonds set the stage for the day with opening remarks about critical hope and intersectionality, paradoxes of hope in times of despair, complexity, and decolonial frameworks. And a panel of NSCSW members at every stage of their careers, from student to retiree, in diverse areas of practice, were invited to share their thoughts on how their personal/professional context intersected with the themes of the conference. Panelists generously shared incredible reflections, grounded in socially just, anti-oppressive, and critical perspectives on social work practice.

In thanks

This conference was made possible through the incredible generosity of our members.

The professional development committee and conference subcommittee spent months developing the event:

- Helen Luedee (Co-chair)

- Rose Scott-Lincourt (Co-chair)

- Lesley Finch

- Joanne Sulman

- Lindsay Murphy

- Kam’la Williams

- Ayeshah Ali

- Marie Westhaver

- Holly Johnson

- Mario Spiler

We are also grateful to the group of panelists who agreed to share their time and insights with their colleagues:

- Rose Scott-Lincourt, Retired Associate

- Ayeshah Ali, Registered Social Worker

- Colin James Morrison, RSW-Clinical Specialist

- Kendall Paul, Social Worker Candidate

- Hannah Long, Student & Social Worker Candidate

Looking ahead

Throughout this province we have thousands of social workers who chose, every single day, to have hope in their interactions with service users, agencies, communities, and society. We saw that throughout the day at our conference

The conversations among conference participants were grounded in socially just, intersectional, and critical social work perspectives. Dozens of attendees co-created a thoughtful and reflective space, deepening our analysis and understanding of critical hope and how it sustains change.

The success of the event and the feedback provided helps us at the NSCSW to better understand how we can support social workers in delivering safe(R) and ethical social work practice in Nova Scotia. We are grateful to all of the members who contributed to the planning, delivery, and evaluation of this event and we look forward to co-creating new and exciting learning engagements in the future.

“It is empowering to know that there are a network of social work colleagues enthusiastically delivering services throughout the province.”

We hope that next year’s conference can be in person, so our members can gather and fully celebrate everything they have accomplished together in the decade since the Nova Scotia Association of Social Workers was transformed into a College in 2016.

If you have additional feedback or thoughts on this conference or future professional development activities, please email Tyler Colbourne at [email protected].